STEAMBOAT DISASTER

- Program

- Subject

- Location

- Lat/Long

- Grant Recipient

-

NYS Historic

-

Event, Site, Transportation

- 51 N Washington St, Athens, NY 12015, USA

- 42.263666, -73.806466

-

Greene County Historical Society

STEAMBOAT DISASTER

Inscription

STEAMBOAT DISASTERTHE STEAMBOAT “SWALLOW”

STRUCK A ROCK AND SANK

NEAR THIS SITE DURING A

STORM ON THE NIGHT OF

APRIL 7, 1845.

WILLIAM G. POMEROY FOUNDATION 2023

The Hudson River serves and served as a vital artery to New York. North to south, the river originates in the Adirondacks; from there, flowing south, it connects Albany to New York City. West to east, the Hudson served as an outlet to the Erie Canal. Beyond its pivotal role in transportation, the river and surrounding landscape also influenced countless artists and writers alike with its awe inspiring ruggedness.

The role the Hudson River played in shaping the State can hardly be overstated; however, the Hudson River could also be the site of tragedy, as was true on the night of April 7, 1845.

According to the 1912 edition of Rand, McNally & Co.’s Illustrated Guide to the Hudson River and Catskill Mountains, steamboats were first introduced to the river circa 1807 (p.21). The steamboat played a major part in further development of the region, allowing for quick and cheap movement of both passengers and goods through New York. This mode of transportation was not without its shortcomings, however. The Hudson River, which contains a number of sand traps and rocks, could pose a tricky route to navigate, especially if the weather was bad and visibility poor.

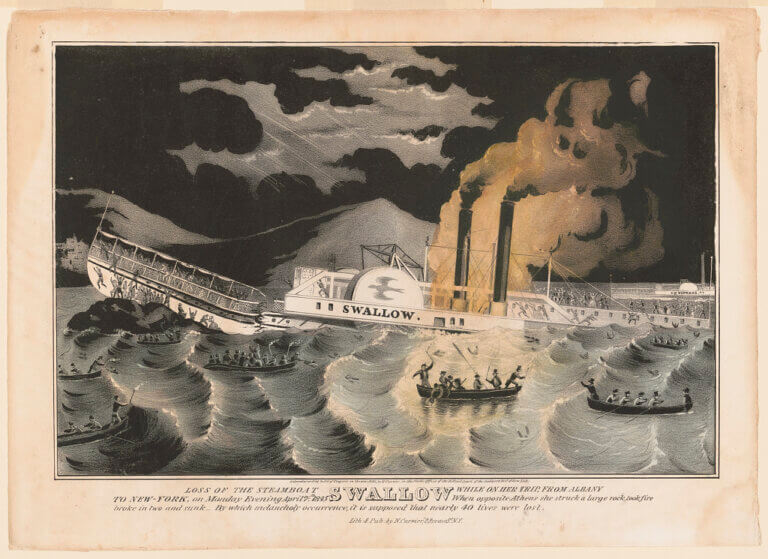

On Friday, April 7, 1845 the Swallow led a trio of steamships on an overnight trip from Albany to New York City, carrying an estimated 250 passengers. Around 28 miles from Albany, amidst gusts of wind and flurrying snow, the Swallow, while navigating around the middle ground flats, struck a large rock. The giant stone and the crash, the former of which would soon be known as Swallow Rock, was described in the subsequent report to the New York State Senate as such:

“The top of the rock is 10 feet above high tide, and 15 feet above low tide, and is about 60 feet by 70 feet in size, at the surface of the water at high tide. At the time of the disaster, the water was about two-thirds ebb tide, and the boat ran up to an elevation of over 33 feet above the surface of the water.” (Senate, Report No 102. April 26, 1845)

The impact of the steamboat against the giant stone was tremendous, and it caused enough damage to nearly split the Swallow in half. Amidst the chaos a number of passengers either tumbled from the boat or jumped into the water hoping to escape the catastrophe, and instead found themselves in the freezing and churning waters of the Hudson. Though initial reports greatly overestimated the number of casualties, the final number of dead likely ranges anywhere from fifteen to around twenty five, with an exact number proving difficult to pinpoint due to the unknown number of passengers onboard that night.

Further loss of life was prevented due to the two nearby steamboats, the Rochester and the Express who were competitors to the Swallow, who aided in rescue efforts following the disaster.