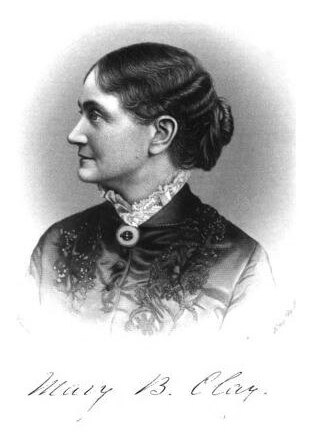

MARY BARR CLAY

- Program

- Subject

- Location

- Lat/Long

-

National Votes for Women Trail

-

People

- 500 White Hall Shrine Rd, Richmond, KY 40475, USA

- 37.8332101, -84.3526553

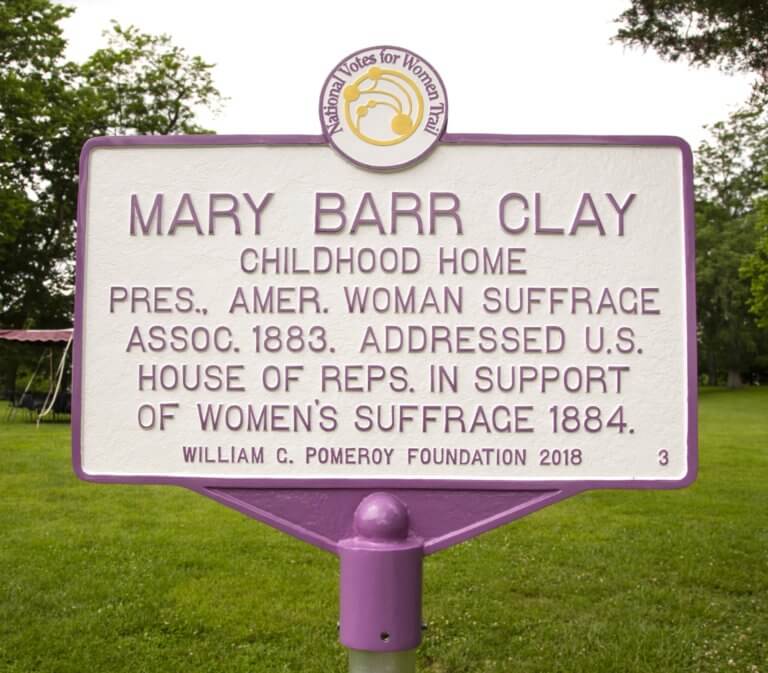

MARY BARR CLAY

Inscription

MARY BARR CLAYCHILDHOOD HOME

PRES., AMER. WOMAN SUFFRAGE

ASSOC. 1883. ADDRESSED U.S.

HOUSE OF REPS. IN SUPPORT

OF WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE 1884.

WILLIAM G. POMEROY FOUNDATION 2018

Born to the prominent Clay family of Kentucky, Mary was the daughter of outspoken abolitionist and U.S. Minister to Russia, Cassius M. Clay. One of the first women in Kentucky to advocate for women’s suffrage, Mary was quickly joined by her sisters, and the youngest, Laura, would eventually become a well-known leader of the movement in Kentucky. Mary was part of both national and state associations, serving as vice president for the National Woman Suffrage Association and vice president and president for the American Woman Suffrage Association. Through those organizations, as well as local ones such as the Kentucky Equal Rights Association, Mary lobbied for female equality among their male counterparts.

Though she was from a family with many well-known and public figures, Mary stated in an article published in The Woman’s Journal on March 2, 1889 that her mother had the largest influence on how she approached the issues with which she dealt. Her mother, Mary Jane, had been born to wealthy slave owners in Lexington, Kentucky, and as a result, grew up in a pro-slavery household. Mary Jane would go on to marry Cassius Clay, who, after going off to college, took up a staunch anti-slavery stance. While living in a Southern, conservative state, being an abolitionist was a dangerous choice, and Mary stated that her mother was her father’s only sympathizer. There were many times were Mary said her mother had to convince her father to stay strong in his beliefs, stating that Mary Jane told him to be prepared to die rather “than give up [his] principles.” Mary Jane’s strong convictions continued through the Civil War, where she was a Unionist in a border state, and after the war, she became a suffragist and supported her daughters’ work to gain enfranchisement. Mary then stated that with a mother such as that, a person “cannot wonder that I, her daughter, should naturally be found advocating the liberty and civil and political equality of women.”

In a short piece on Mary in A Woman of Century: Fourteen Hundred-seventy Biographical Sketches Accompanied by Portraits of Leading American Women in all Walks of Life (1893), her revelation about women’s place in society came after attending a convention held in Cleveland, Ohio, where she saw Lucy Stone speak sometime around 1868 and 1869. From that point on, Mary began to not only read pamphlets and books published on the topic of gender inequality, but she began to write her own pieces and submit them to newspapers. Along with written articles, Mary also spoke to legislatures at both the state and national level about the need for political equality for women.

One such speech before the U.S. House Judiciary Committee, given on March 8, 1884 and recorded in History of Woman Suffrage (vol. IV), saw Mary pleading for change on behalf of women, noting that it was like a debate between “a subject class with a ruling class.” Continuing on in her speech, Mary noted the disparity in treatment of men and women, stating that up until they come of age, boys and girls are treated the same. After that point, however, a “boy becomes a free human being” and “the girl remains a slave, a subject.” This leaves women without the ability to vote and therefore “powerless either to punish or reward.” To conclude her speech to the Judiciary Committee, and to summarize her belief in why women needed enfranchisement, Mary stated that men needed a woman’s “sense of justice and moral courage,” while women needed “the ballot for self-protection.”

As of 2019, the marker dedicated to Mary Barr Clay stands outside White Hall Historic Site, which is where she lived growing up.