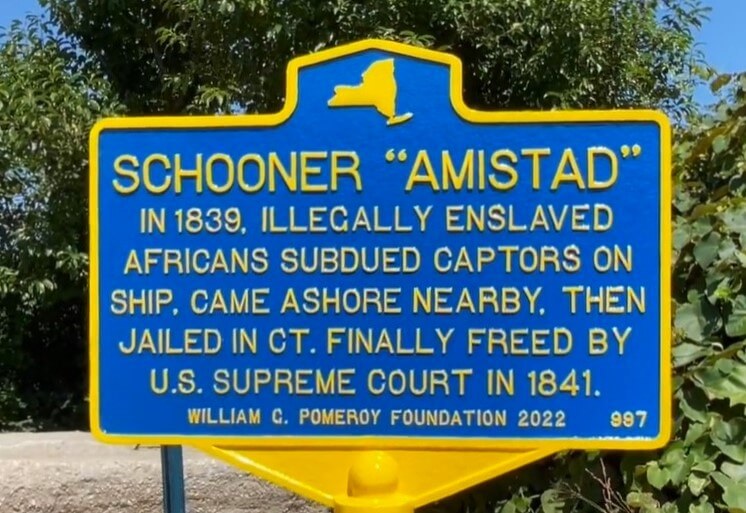

SCHOONER “AMISTAD”

- Program

- Subject

- Location

- Lat/Long

- Grant Recipient

-

NYS Historic

-

Event, People, Site

- 185 Soundview Dr, Montauk, NY 11954, USA

- 41.071233, -71.95855

-

Montauk Historical Society

SCHOONER “AMISTAD”

Inscription

SCHOONER "AMISTAD"IN 1839, ILLEGALLY ENSLAVED

AFRICANS SUBDUED CAPTORS ON

SHIP, CAME ASHORE NEARBY, THEN

JAILED IN CT. FINALLY FREED BY

U.S. SUPREME COURT IN 1841.

WILLIAM G. POMEROY FOUNDATION 2022

In June 1839, a group of 53 illegally enslaved Africans were sold to Spanish subjects Jose Ruiz and Pedro Montez in Cuba and put aboard the schooner Amistad at Havana. The Africans, 49 men and four children, were Mende-speaking people from neighboring villages in West Africa. They had been captured that April and brought to Cuba to be sold as slaves. This was despite a December 1817 edict issued by the King of Spain for the abolition of the slave trade making it illegal for slaves to be imported into any Spanish dominions.

The Amistad set off from Havana bound for another province of Cuba, loaded with cargo, provisions, money, and the illegally enslaved Africans. Once at sea, the Africans took control of the Amistad, killing the captain along with another member of the crew. Two other members of the crew abandoned the vessel, but Ruiz and Montez were spared, so they could navigate the Amistad back to Africa.

Unbeknownst to the Africans, rather than Africa, Ruiz and Montez sailed the Amistad north, toward the east coast of the United States and by August, they had reached Long Island. While anchored approximately a half mile off the coast at Culloden Point, some of the Africans came ashore looking for water and provisions. The U.S. Coast Survey Brig Washington, commanded by U.S. Navy Lieutenant Thomas R. Gedney, spotted the Amistad and the Africans coming ashore. Gedney seized the vessel and brought it to a port at New London, Connecticut. The Africans, charged with murder and piracy, were jailed. An account provided by Joshua Leavitt, an abolitionist who visited the Africans while they were imprisoned in New Haven, was published in the September 13, 1839 edition of The Liberator. Leavitt noted that even the children, “three girls and one boy,” were detained “in a room by themselves” at New Haven.

While the charges of murder and piracy were dismissed, the Africans continued to be held in custody due to claims filed on them as property. Gedney, along with the officers and crew of the Washington, filed a claim on the Amistad, its cargo, and the Africans under the law of salvage. Additional claims were filed by Ruiz and Montez, as well as the United States, at the insistence of a minister of Spain who demanded the Africans, the vessel, and its cargo be “returned” to their Spanish “owners.”

With the assistance of a translator named James Covey, the Africans filed an answer to the property claims and contended that since they were born free in Africa, they were not the property of Ruiz or Montez. They recounted being kidnapped in Africa, carried in a slave ship to Cuba, sold to Ruiz and Montez, and then put on the Amistad as slaves. The District Court of Connecticut dismissed all property claims on the Africans and decreed that they should be delivered to the President of the United States in order that they may be transported back to Africa.

Despite the District Court ruling, the Africans were still not freed. In April 1840, the U.S. Attorney for the District of Connecticut appealed the decree to the Circuit Court of Connecticut. The Circuit Court affirmed the decree of the District Court, and the U.S. Attorney then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The case went before the Supreme Court in January 1841. Former President John Quincy Adams represented the Africans. In his argument before the Supreme Court, delivered on February 24 and March 1, Adams stated:

“The whole of my argument to show that the appeal should be dismissed, is founded on an averment that the proceedings on the part of the United States are all wrongful from the beginning. The first act, of seizing the vessel, and these men, by an officer of the navy, was a wrong. The forcible arrest of these men, or a part of them, on the soil of New York, was a wrong. After the vessel was brought into the jurisdiction of the District Court of Connecticut, the men were first seized and imprisoned under a criminal process for murder and piracy on the high seas. Then they were libelled by Lieut. Gedney, as property, and salvage claimed on them, and under that process were taken into custody of the marshal as property. Then they were claimed by Ruiz and Montez and again taken into custody by the court.”

Adams continued:

“The captives of the Amistad were, when taken by Lieut. Gedney, not even in the condition of slaves; they were freemen, in possession not only of themselves, but of the vessel with which they were navigating the common property and jurisdiction of all nations, the Ocean; in possession of the cargo of the vessel, and of the Spaniards Ruiz and Montez themselves.”

In March 1841, the Supreme Court affirmed the decree of the Circuit Court, excepting the part that said the Africans should be delivered to the President of the United States, which was reversed; the Africans were finally freed. The Supreme Court opinion read in part:

“It is plain beyond controversy, if we examine the evidence, that these negroes never were the lawful slaves of Ruiz or Montez, or of any other Spanish subjects. They are natives of Africa, and were kidnapped there, and were unlawfully transported to Cuba, in violation of the laws and treaties of Spain, and the most solemn edicts and declarations of that government. By those laws, and treaties, and edicts, the African slave trade is utterly abolished; the dealing in that trade is deemed a heinous crime; and the negroes thereby introduced into the dominions of Spain, are declared to be free.”

According to the December 7, 1841 edition of the New York Tribune, after their illegal enslavement and subsequent imprisonment in the United States, only 35 of the Africans survived to sail to Sierra Leone aboard the Gentleman with a group of American missionaries in November 1841. According to the Tribune, two had been killed while taking control of the Amistad, seven died aboard the Amistad, eight died at New Haven, and one died while in Farmington, Connecticut awaiting passage to Africa. The surviving Africans reached Sierra Leone in January 1842.