- Program

- Subject

- Location

- Lat/Long

- Grant Recipient

-

NYS Historic

-

People

- 1 River Road, Ulster Park, NY

- 41.900041, -73.97402

-

Ulster County Historical Society

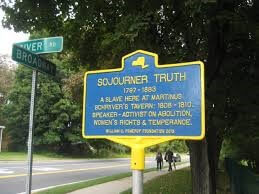

SOJOURNER TRUTH

Inscription

SOJOURNER TRUTH1797-1883

A SLAVE HERE AT MARTINUS

SCHRYVER'S TAVERN: 1808-1810

SPEAKER-ACTIVIST ON ABOLITION

WOMEN'S RIGHTS & TEMPERANCE

WILLIAM G. POMEROY FOUNDATION 2013

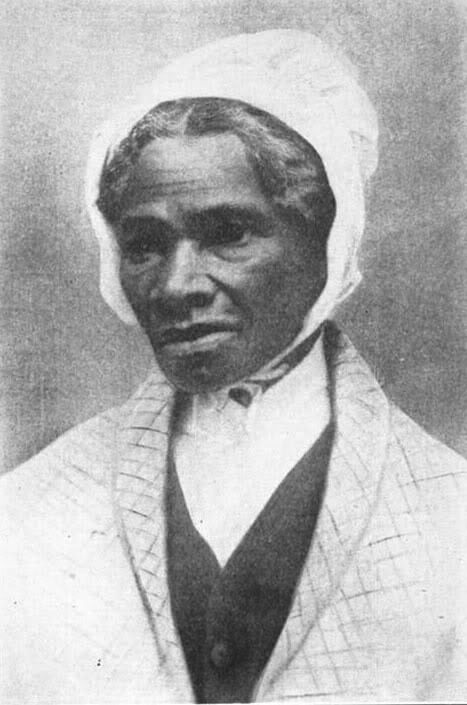

Sojourner Truth, a prominent African-American abolitionist and women’s rights activist, lived in this stone structure, a former tavern, between 1808 and 1810. At that time, it was owned by Dutch innkeeper, Martinus Schryver, to whom Sojourner Truth was bound as a slave. She was later sold by Schryver to John Dumont, until Sojourner Truth made her walk to freedom in 1826, a year before she was legally emancipated by state legislation.

Sojourner Truth was born sometime between 1797 and 1800 in Swartekill, present day Rifton, NY. Her name by birth was Isabella, and she was the daughter of slaves James and Betsy, aka Bomefree and Mau-mau Bett. At the time of her birth, Sojourner and her parents were enslaved under a Colonel Ardinburgh, who died when Sojourner was an infant. The colonel’s son, Charles Ardinburgh, inherited his father’s property including the enslaved Isabella and her parents. The Ardinburghs, like many families in the area, were Dutch and Sojourner Truth’s first language was Dutch. Charles moved into a new house for a hotel and the family of Sojourner had to live in a damp cellar with loose floorboards poorly covering noxious mud and water. Bomefree and Betsy had two children before Sojourner, but they were taken from them and sold when Sojourner was an infant. Mau-mau Bett taught Sojourner to pray as a source of respite and aid during their suffering as slaves. (Narrative of Sojourner Truth, 1850)

When Charles Ardinburgh died, his property was put to auction, including those enslaved under him. But because of Bomefree’s decrepitude, caused by the neglect and overwork of life as a slave, nobody was willing to buy his servitude. Instead the decision was made to emancipate Betsy with the stipulation that she take the responsibility of caring for Bomefree, which she did until her death. They would continue to live in the same damp cellar of the hotel which was sold to new owners. The young Sojourner, however, was sold along with Ardinburgh’s sheep to John Neely for $100. (Narrative of Sojourner Truth, 1850)

Unlike the previous slave-masters in Sojourner’s life, Neely, a trader near Kingston, NY, did not speak Dutch. He would brutally whip and abuse her when she was unable to understand his orders. Sojourner Truth would bear a lattice-like network of scars on her shoulders and arms for the rest of her life, and she would sometimes display these to audiences of her lectures, especially to silence racist hecklers. (Mabee, 1993) While she suffered under the brutality of Neely, Sojourner would often pray for her father to return and give her deliverance. Finally, one day, he actually did visit, travelling 15 miles to Kingston. Neely did not allow them to meet privately but, as Bomefree was leaving, Sojourner recalled that she “unburdened her heart to him” and begged him to take her. He couldn’t take her with him, but he promised that he would try to find a better place for her. At the time, it was reportedly a custom of the Dutch to allow indentured servants and slaves to solicit a new owner, and Bomefree and Mau-mau Bett would ask trusted Dutch families after church services or after performing odd jobs for them, emphasizing the cruelty of Sojourner’s English master. (Margaret Washington, 2009)

Bomefree’s promise was fulfilled when Martinus Schryver, a Dutch fisherman and innkeeper, bought Sojourner from Neely for $105. Schryver had never owned any slaves before but agreed to Bomefree’s request to buy his daughter. (Margaret Washington, 2009) Schryver’s tavern was found on the road parallel to the Hudson River, near modern day Port Ewen. (Colles, 1961) Life at Schryver’s inn was a significant adjustment for Sojourner. While Schryver’s lower-class Dutch clientele were reportedly crude and taught Sojourner to curse, she suffered none of the physical abuse and torture that Neely committed, and she did not find her work too taxing. Sojourner had relative freedom to roam while performing errands and gathering vegetables, and she would often watch the boats on the Hudson. (Mabee, 1993) She even reported seeing some of the first steamships to navigate the river. (Narrative of Sojourner Truth, 1850) It was here, during a ball held at the tavern, that much of Sojourner’s lifelong passion for singing was kindled. (Mabee, 1993)

Sojourner Truth’s relative reprieve from the worst tortures of slavery, afforded by her time at Schryver’s tavern, would prove short lived though. Schryver ran into financial problems, defaulting on land payments in November of 1810, and in May of the next year some of his lands were seized from him. This may have played a role in his decision to sell Sojourner for $200 to John Dumont in 1810, double the amount Schryver paid to Neely. (Margaret Washington, 2009)

Sojourner Truth would remain enslaved under John Dumont until the year before her emancipation by state legislation, which took place in 1827. (New Paltz Times, 1883) John Dumont had promised to free Sojourner Truth a year before the state manumission act in recognition of her loyal service. However, he broke his word at the last minute, claiming an injury to her hand decreased her productivity. Sojourner later recalled in her narrative that this tactic, to offer promises of freedom or permission to visit loved ones only to renege later, was commonly used by slavers to manipulate and motivate slaves,. (Narrative of Sojourner Truth, 1850)

Incensed and desperate for freedom, after remaining several weeks and performing what work she felt obliged to, Sojourner walked in the morning daylight away from slavery forever, taking refuge at the home of the Van Wageners. (Narrative of Sojourner Truth, 1850)