SUFFRAGIST

- Program

- Subject

- Location

- Lat/Long

- Grant Recipient

-

NYS Historic

-

People

- 262 3rd Ave, Troy, NY 12182, USA

- 42.762791, -73.681425

-

Lansingburgh Historical Society

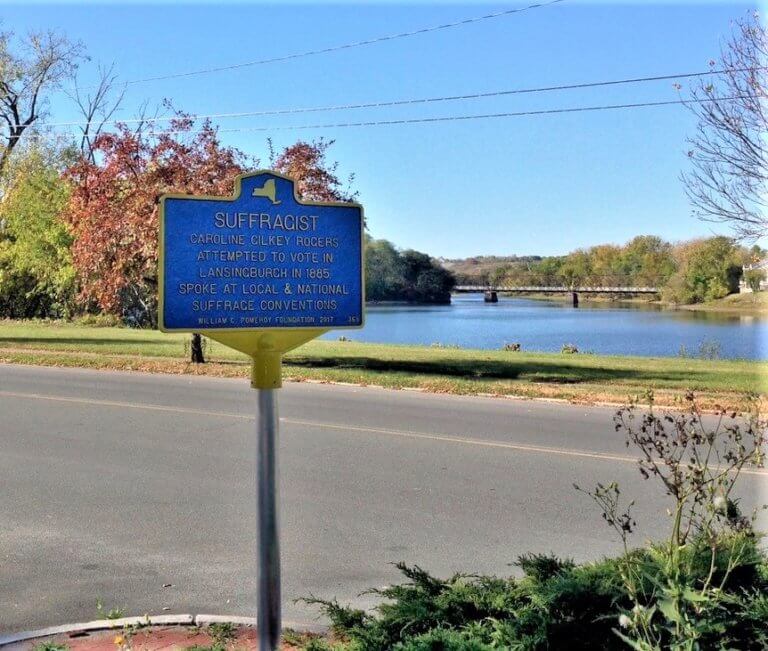

SUFFRAGIST

Inscription

SUFFRAGISTCAROLINE GILKEY ROGERS

ATTEMPTED TO VOTE IN

LANSINGBURGH IN 1885.

SPOKE AT LOCAL & NATIONAL

SUFFRAGE CONVENTIONS.

WILLIAM G. POMEROY FOUNDATION 2017

Caroline Rogers (ca. 1837-1899) was a prominent suffragist who attempted to vote in 1885 in the village of Lansingburgh (now part of the City of Troy). She spoke at local and national women’s rights conventions. Rogers also hosted suffrage meetings at her home, including welcoming leaders such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton.

A genealogy of her mother’s family states that Caroline was born in Camden, Maine on May 4, 1837 to Caleb Gilkey and Belinda Pendleton Gilkey. The U.S. Census for 1850 records the Gilkey family still residing in Camden at that time, but in 1860 Caroline entered her first marriage with a man named Cyrus Clark in Boston, Massachusetts. (Register of Boston Marriages, 1860) She remarried on August 19, 1880 to Elias Rogers of Troy, New York (Register of Boston Marriages, 1880) and they relocated to Lansingburgh around 1881. Elias was a widower who ran a specialized laundry service in Troy, and it was in this city that Caroline became heavily involved in the women’s suffrage movement, organizing a chapter of the New York State Woman Suffrage Association and soon embarking on speaking tours throughout New England. Known as Carrie to her friends and family, she was also a portrait painter by trade in addition to being a suffrage activist. (Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton & Susan B. Anthony, 2006, 2009)

Caroline quickly became a key driver of suffrage and woman’s rights activism in both the city of Troy and the state of New York generally. During the 1880s she addressed state meetings of suffrage organizations, managed a local school board campaign, lobbied the legislature and hosted nationally renowned suffragists such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton. (Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton & Susan B. Anthony, 2006, 2009) She would also help and encourage women to vote or attempt to vote, even using her own horse named Jessie to carry women to the polls on at least one occasion. (New York Evening Telegram, 1882)

Her most notable act was an attempt to vote in 1885. That year the members of the New York Woman’ Suffrage Party organized women to publically attempt voting in cities across the state, including in Albany, Ithaca, Ogdensburg, and Utica, among others. (New York World, 1885) Caroline participated in this effort in Lansingburgh as well. She recounted the experience in remarks before a State Assembly Committee on Grievances:

“A short time ago a call was issued for all taxpaying inhabitants to come out and vote upon the question of introducing the water works into the village. Being very anxious for this measure to be carried I went with a lady friend to the polls, but our ballots were refused, and when I pointed out to the inspector that ‘all taxpaying inhabitants’ were urged to come, he said: ‘oh that does not mean women.’ “ (Daily Saratogian, 1885)

Caroline’s political perspective was very much in line with the mainstream of the National Woman Suffrage Association and its prominent leaders such as Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. She stated that the ballot was “…the symbol of equality” and argued that the entry especially of educated and professional women was necessary for the moral and political health of the nation. While she was dedicated to winning equal rights and the ballot for women, she also sometimes appealed to racial and class prejudices towards these ends. For example, she argued before a US Senate select committee on Woman Suffrage in 1884 that she found it humiliating that a “colored man”, naturalized immigrant, or illiterate had a vote when she and other educated white women did not. (Woman Suffrage, 1913) This was a common tactic resulting from controversy and debate over the 15th amendment, which many early suffragists hoped would grant the vote to women in addition to African-American men, with Carrie Chapman Catt, for example, arguing that winning over white wealthy women in the south was a strategy for convincing the south to support a constitutional amendment for women’s suffrage. (Woman Suffrage by Federal Constitutional Amendment, 1917)

Caroline continued to play a leading role in the New York Suffrage movement through the 1890s until the end of her life. She died in Brooklyn on November 12, 1899 (NYC Municipal Death Record, 1899) and her remains were brought to Troy by boat two days later. A funeral was then held at Earl Memorial in Oakwood Cemetery. (Troy Daily Times, 1899) A historic marker funded by the William G. Pomeroy Foundation was erected in 2017 near the site of her former home in what is now Troy, New York.